Powstanie Warszawskie

I’ve written an earlier article about a relatively unknown battle of World War II – the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. However, that was not the only great tragedy to befall Warsaw during World War II.

A bit over 15 months later, a second and larger uprising occurred in Warsaw – the Warsaw Uprising. Like the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, it is today not well known.

But unlike the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the later Warsaw Uprising was not simply a choice between dying in place and dying in a Nazi extermination camp. While it was a desperate venture likely to end in failure, it was nonetheless a bona fide effort to liberate the city from Nazi control.

It failed because the anti-Nazi Polish forces were callously abandoned – by some of their supposed Allies. Soviet forces were at the time less than 10 miles away, in the eastern suburb of Wolomin.

Until it was far too late, they made no attempt to assist.

Background

On 22 June 1944 – not coincidentally, the third anniversary of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa – the Soviet Offensive of 1944 (Operation Bagration) began. This offensive was wildly successful, and pushed German forces out of Belorussia, the western Ukraine, most of Lithuania, part of Latvia, and eastern Poland, and was threatening to cut off German forces in Latvia and Estonia. By 29 July, Soviet forces had reached the eastern suburbs of Warsaw approximately 15 kilometers east of the city center.

The pro-Western Polish government-in-exile determined that the time was right to attempt to free Warsaw from Nazi occupation. They ordered the Polish Home Army to cooperate with Soviet forces in freeing Warsaw, and to initiate the Warsaw Uprising.

The Uprising Begins

The Polish Home Army was ill equipped for combat, even in an urban environment such as Warsaw. On 1 August 1944 – the day the Warsaw Uprising commenced – their military arms consisted of:

- 1,000 guns

- 1,750 pistols

- 300 submachine guns

- 60 assault rifles

- 7 heavy machine guns

- 20 anti-tank guns

- 25,000 hand grenades

Nazi forces in Warsaw were mostly lightly-armed occupation troops. However, Nazi forces in the general area included infantry and panzer divisions.

Moreover, Warsaw had been designated to serve as a major defensive center for German forces in Poland, to be held at all costs. In late July, after being soundly defeated and driven back by Soviet forces and the unsuccessful attempt on Hitler’s life, Nazi forces were somewhat disorganized and demoralized. However, these forces were reinforced prior to the end of the month.

Soviet forces advancing on Warsaw also at this time began a propaganda campaign calling for a general uprising in Poland. Nazi authorities in Warsaw also began conscripting civilian labor to work on Warsaw fortification projects. Thus, the leadership of the Polish Home Army – the Armia Krajowa – opted to begin the Warsaw Uprising on 1 August 1944.

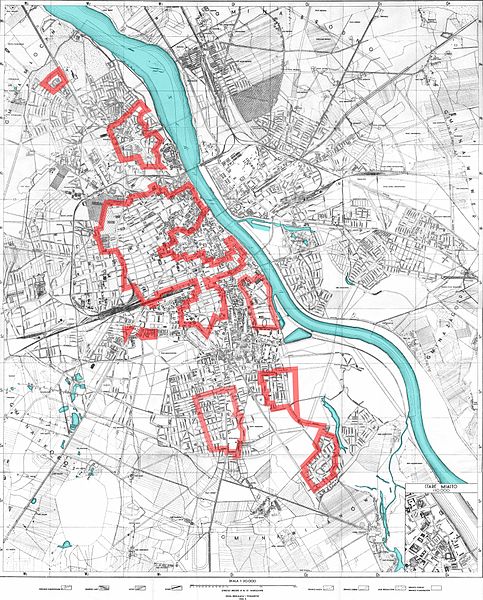

Initially, even in spite of limited resources the uprising was relatively successful. The uprising caught German forces off-guard, and was successful in seizing a large portion of the western part of Warsaw. (Though allowing for the possibility of unrest, local Nazi forces were surprised by the size and scope of the rebellion and were forced to retreat westward for the first 3 days.) By 4 August, the Polish Home Army Forces had seized the areas noted in red on this map to the west of the Vistula River (the Vistula runs generally south-to-north, and splits the Warsaw metro area):

The hope was that Soviet forces would advance and link with the Polish Home Army forces, driving Nazi forces out of Warsaw and liberating it. Sadly, that was not to happen.

Predictably, the Nazis reacted with a heavy hand. Their forces began receiving reinforcements, and stopped retreating. They then began counterattacking with typical disregard of civilized behavior.

Nazi forces then perpetrated the Wola massacre and the Ochota massacre. Between 5 and 14 August (Wola), and between 4 and 25 August (Ochota), these western districts of Warsaw – held by rebel forces – were surrounded by Nazi forces including the notorious SS-Sturmbrigade Dirlewanger and Russian SS collaborators from the SS Sturmbrigade Russian National Liberation Army (the acronym in Russian transliterated to German is typically given as “RONA”), AKA “the Kaminski Brigade”. The two districts were razed, and it is estimated that between 50,000 and 100,000 civilians were slaughtered – the overwhelming majority of whom were noncombatatants.

Continued Resistance

Though the massacres took a terrible toll, the atrocities strengthened Polish resolve. Polish Home Army forces continued to hold many enclaves in western Warsaw – including the Old Town. They held on tenaciously.

However, without allied help – and supplies – the result was a foregone conclusion. German forces continued to constrict and compress the enclaves held by rebel forces. Old Town fell on 10 Sepember. Yet even at this late date, Polish Home Army forces held a substantial part of Warsaw west of the Vistula.

In fact, the Soviets did little more than stand by and watch their “allies” be killed. Though they allowed Polish Communist forces fighting with the Red Army (the 1st Polish Army) to attempt to fight through and assist their brethren fighting west of the Vistula, they only halfheartedly and reluctantly supported this effort. Moreover, the Soviets actively impeded efforts by British and US forces to support them. The Soviets refused permission for other Allied forces to land in or operate out of bases in Soviet-held territory, and on at least one occasion actually fired on Allied aircraft which overflew their positions east of Warsaw. On 18 September, the Soviets finally gave permission for the US to use Soviet airfields – once – in conjunction with aerial resupply for the Warsaw Uprising. (Permission was again granted near the end of September, but by then the weather had turned and aerial resupply – which requires good flying weather – was no longer possible.)

Though ground support was impossible, British air forces (including Polish forces operating with the RAF) attempted to resupply Polish forces in the uprising nonetheless. Because of the Soviet refusal to cooperate in this effort, the operations were launched from bases in England and Italy, severely degrading their effectiveness and leading to rather substantial losses (approx. 12%). Nonetheless, over 200 sorties were made dropping supplies to the beleaguered Poles in western Warsaw.

Unfortunately, only somewhat less than half of the supplies reached Polish forces. The rest were lost or fell into German hands.

Finally, in on 26 August – after the Polish Home Army had been fighting without ground assistance for in excess of 3 weeks – the Soviet offensive resumed. By 13 September, Soviet and Polish 1st Army forces (fighting with the Red Army under Red Army control) had effectively occupied Warsaw east of the Vistula. The Soviets allowed Polish 1st Army Forces to attempt to cross the Vistula on multiple occasions between 14 and 23 September, but provided only scant artillery and air support. Casualties were heavy; only approximately 900-1,200 made it across, and these were relatively ineffective.

These operations were then curtailed by order of the Soviet high command, and Polish 1st Army troops that had crossed the river were essentially abandoned (they were never reinforced or evacuated, and only a handful were able to recross to the eastern bank of the Vistula). In attempting to assist their countrymen fighting in western Warsaw, the Polish 1st Army suffered over 5,600 casualties (KIA/MIA/WIA). They also lost their commander, who was relieved by the Soviets – presumably to replace him with someone more compliant with Moscow’s desires. Perhaps he’d acted contrary to orders in attempting to assist his countrymen in the first place.

The Soviets then stood by doing nothing as the remaining enclaves in western Warsaw fell. Attempts at aerial resupply of Polish forces in western Warsaw were halfhearted and ineffective, and no further attempts were made to cross the Vistula. The uprising ended when the final Polish Home Army enclaves surrendered on 2 October 1944 – 62 days after the uprising had begun.

Aftermath

After the uprising, the portions of Warsaw west of the Vistula were essentially depopulated by the Nazi government. It is estimated that 85% of pre-war Warsaw was then destroyed – if it had not been destroyed during the initial conquest in 1939, during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising the previous year, or during the Warsaw Uprising itself, it almost certainly was afterwards.

The Soviets did nothing in response. They did not resume offensive operations in Warsaw until January 1945 – at which time Warsaw fell quickly.

Why?

“Why?” suggests two different questions, each of which has a different answer. The first is, “Why did the uprising occur at all?” The second, “Why did the Soviets stand by and do nothing?”

The first is easier to answer. The Polish Home Army – and the west-leaning Polish government-in-exile – had received reports from areas of Poland that had been “liberated” by the Soviets. In those areas, the Polish Home Army and supporters of the Polish government-in-exile had been effectively liquidated.

The Soviets initially allied themselves with Home Army units in areas they were attacking, using them by to help liberate cities and other areas of importance. They then incarcerated these units, imprisoned their officers (as well as other prominent supporters of the Polish government-in-exile), and gave the troops a stark choice: join the Red Army and fight the Nazis or be sent to a labor camp. In essence, the process of “Sovietization” of Poland (and of the rest of Eastern Europe) had begun.

At that point, the Polish Home Army and government-in-exile knew that waiting for the Soviets to liberate Warsaw was simply exchanging one foreign conqueror for another. The only choice that offered hope was to take a desperate chance – one that might well end in death, but which nonetheless offered some slim chance for freedom.

As to why the Soviets stood by and did nothing: many theories have been offered. Most fall along three lines. Soviet apologists point out the fact that the Soviet offense was by that time was spent, and in fact was pushed back a few kilometers from Warsaw in mid-August by Nazi counterattacks. They also claim a “strategic pause” and/or a redirection of effort to the upcoming summer-fall campaign to clear Romania and Hungary.

IMO, these claims have little validity, and are little more than apologia. Though they had clear knowledge of the uprising, orders from the Kremlin for a Soviet halt in the vicinity of Warsaw were issued on the same day that the Warsaw Uprising began. German defenses in the area were also largely disorganized and demoralized in early- to mid-August 1944. Soviet conduct in areas of Poland occupied by Red Army forces clearly show they had no intention of cooperating with (or even allowing) any pro-Western Polish organizations. The Soviets also were waging a propaganda campaign in June and July urging Poles to resist Nazi occupation. Finally, the Soviet refusal to allow other Allied forces to use airstrips in Soviet-held territory for resupply efforts until the latter part of September (after the issue had been effectively decided) IMO further indicates the true reason.

All of the above taken together IMO points to a single, disgusting conclusion: the Soviets used the Nazis to do their dirty work. Specifically, they consciously used the Warsaw Uprising to eliminate a large, organized group that was formed a potential post-war Polish opposition to Soviet rule – while simultaneously also damaging their Nazi enemies. They callously and intentionally stood by and allowed fellow anti-Nazi Allies to be slaughtered because they might have posed a post-war problem for the Soviets.

A Postscript.

With the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union, Poland did at last become truly free again – though the residuals of both Nazi and Soviet occupation echo even today.

One side of my family hails from that part of Europe. I have somewhat distant relatives there, and in a neighboring state. But my connection with Europe is tenuous at best. That past is not mine; I do not speak Polish or other Slavic languages.

My father, however, did as a child; his parents were immigrants, and that was the first language he learned. (Both of these grandparents passed away before my birth, unfortunately.) And late in life, because of the changed world situation my father had the opportunity to visit surviving family in Poland – something that was effectively impossible for decades.

It turns out my father and one his brothers were not the only ones of his generation in the family who’d made the military a career. One of my distant cousins – one about my father’s age – apparently had become an officer in the Polish Army, and had made that his career as well.

Sadly, he remembered the time under the Communists as good ones – after all, as an Army officer he’d been an apparatchik. Yet there’s a question my father never asked him but I wish he had, over a beer or two: “Had war come, which way would you have pointed your guns and your tanks? To the west . . . or to the east?”

Given history, I suspect there’s a fair chance it wouldn’t have been to the west.

Notes on Sources:

For once, the Wikipedia articles on the Warsaw Uprising appear a fairly good source. Though perhaps a bit more apologetic towards Soviet inaction than I find warranted, they do appear to give a good overview of the situation, operations, and background concerning the uprising.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warsaw_Uprising

Many of the articles linked within that article give further details. All in all, IMO a credible effort on Wikipedia’s part.

The Wikipedia Articles on the Wola and Ochota Massacres, the SS-Sturmbrigade Dirlewanger and SS-Sturmbrigade RONA are similarly good overviews.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wola_massacre

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ochota_massacre

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS-Sturmbrigade_Dirlewanger

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S.S._Sturmbrigade_R.O.N.A.

There are also a number of other good articles and Internet sites detailing the Warsaw Uprising – many with an ideological bent and/or in Polish. These in particular appear to be good English-language ones.

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/warsaw_uprising_of_1944.htm

http://www.warsawuprising.com/

Category: Historical

Very good as usual Hondo. In 1996 I went on a study abroad trip to Poland, Slovakia and Hungary, during which we spent the lion’s share of the time in Poland (probably 2 out of the 3 weeks that we were there). I met many distinguished Poles-including a man named Stanislaw Macksa who was our guide at Auschwitz (he spoke English, Latin and ancient Greek and had been a language teacher after the war) who had been incarcerated in a labor camp by the Nazis. He had not much good to say about either the Germans or the Soviets and almost every Pole we talked to (I can only think of one exception) hated the Communists. My impression was that the nation was stirring itself from a long unpleasant period and was happy to be taking its place among the free nations of the world. I would be curious to return and see what they are like today.

Great write up, and thank you! Interesting to note is that the resistance was begging the Allies to airdrop in the Polish Brigade, but Montgomery refused because he wanted them for Market-Garden.

I do fully agree with you that the Russians willfully sat on their laurels and allowed the slaughter to occur. For some reason, a majority of historians don’t want to call an apple an apple, and leave that part out of the story.

For an excellent and stirring movie regarding the Warsaw occupation, I’d highly recommend the movie “The Pianist.” Excellent film, plus it’s based on a true story. I’m almost positive it’s on Netflix.

My mother’s side of the family is predominantly Polish. Definitely on my bucket list to go there.

Not too surprising that the Soviets deliberately sat on their hands to let the Germans destroy the Polish Home Army in Warsaw. Don’t forget that the Soviet NKVD massacred over 22,000 captured Polish officers in Katyn Woods in May 1940, basically eliminating most of the people that made up the Polish intellectual and technocratic classes (most of the Polish officers killed were reserve officers who were leaders in Polish civilian society). It was not until 1991 that the Russians admitted to the Katyn Massacre, after blaming it on the Nazis for 51 years. The Soviets basically wanted a Poland denuded of any actual or potential leaders that were not hardcore communists bred in Moscow, Allowing the Werhmacht/SS to destroy the Polish Home Army was just a means to that end…

Thanks for posting on this. My grandfather was a Polish Cavalry officer in 1938. He was part of the Home Army resistance although at the time of the uprising, I think he was already in a German POW camp in Germany. After the war, he stayed in Germany since there was nothing left in Poland to go home to. He married a German woman who had been a nurse at the POW camp. Eventually they came to the US. He dies just before I was born. He had severe health problems later in life. We always attributed that to the conditions and malnutrition of the resistance followed by worse in the camp.

From the Soviet point of view, you had Poles (whom they didn’t like and would just as soon seen totally eliminated) getting beat upon by Germans (whom they didn’t like and would just as soon see totally eliminated.) A great example of successful realpolitik from the Russian’s point of view.

To be a bit callous about things – think “Syria”.

Having spent part of my life in the USSR as a Jew, I can also tell you that historically and culturally, the Soviets hated the Jews. Even though the Soviets considered the Germans (they still played “Reds vs. Whites,” Reds being the Soviets and Whites being the Germans when I was a kid) their mortal historic enemies, I would submit that the Germans were doing the job the anti-Semitic Soviets weren’t doing – annihilating the Jew problem. That’s in addition to not liking the Poles. There were longer term objectives at play here. The Soviets would have a lot more influence in Poland if the Poles were trampled by the Germans.

I’ve always considered the Soviet and, later, Russian nationalism as very similar to German nationalism during WWII.

Just my 2 cents.

[…] his return to the Polish Home Army, Pilecki maintained contact with ZOW. However, when the Warsaw Uprising began in August 1944, Pilecki volunteered to take part. He first fought incognito in the northern […]