Hell and High Water

Gettysburg.

To any American with even a rudimentary knowledge of military history, that word speaks volumes. The battle itself, its historical impact, the heroism, the second-guessing . . . . all of these are legendary. Literally hundreds of books have been written concerning various aspects of the battle and its aftermath.

Yet certain parts of the battle remain under-appreciated today. That’s true even of some that are well-known.

In fact, that’s true for one of the great acts of heroism which occurred at Gettysburg. IMO, it’s one of the greatest acts of collective heroism in military history – ranking with Gideon’s Band, the Spartans at Themopylae, and the Charge of the Light Brigade. Yet it is an action for which none of the participants received any substantial personal recognition other than after-the-fact praise. The human cost was extreme. And it remains controversial even today.

But that’s to be expected. Any military operation involving 52+% casualties should be expected to have both heroic and controversial aspects. That’s especially true when it involves roughly 12,500 men.

I’m referring to Pickett’s Charge.

Background.

Gettysburg – and the US Civil War – came at a time where technology had provided the means to change the nature of ground combat. However, doctrine and tactics had not yet caught up with changed technology. The result was a war fought often with old-style tactics using more modern weapons.

Predictably, the results were horrific.

Napoleonic-era formations and tactics largely persisted. This was true in spite of the continued advances in artillery (dramatically more accurate, with better anti-personnel capability) and the mass adoption of rifles vice smoothbore muskets by infantry. Between those two recent developments, troops could now accurately engage and kill each other at ranges of hundreds of yards vice only at close range. Further, additional technical developments – such as repeating rifles and fused shells – added to the vulnerability of exposed soldiers and the potential lethality of a prepared defender.

In short: war had transitioned from an era favoring elan and offense (the Napoleonic era) to one favoring preparation and defense. The defender could now kill at long range, from a concealed position. And if/when attackers massed, they could be killed on an industrial scale – quickly.

Leadership on both sides seemed slow to recognize or embrace these changes. A brief look at the Confederate leadership is illustrative. After a brief bit of defensive orientation early in the war – and after being derided as the “King of Spades” for same – Lee reverted to the Napoleonic model of the attack. Jackson focused on speed and audacious maneuver – and reportedly requisitioned pikes for at least some of his troops. The same was true of most other senior Confederate generals.

Longstreet seemed to understand the magnitude and impact of the changes, as well as grasping how they dictated the beginnings of modern small-unit infantry tactics (coordinated combination of fire and maneuver by small elements; use of field fortifications and trenching; and the inherent advantage offered the defense given the weapons of his day). But Longstreet was not an eloquent speaker, and was unable to persuade.

Longstreet was also not in overall command of Confederate forces at Gettysburg; that was Lee. But in an ironic twist of fate, it was Longstreet who was fated to give the final approval for Pickett’s charge.

Gettysburg.

I won’t rehash the entire 3-day battle in detail here; various works do so far better than can I. But a summary may be helpful to set the stage.

Day 1 was the meeting engagement that began the battle. Buford’s inspired early defense east of Gettysburg forced a premature Confederate deployment, buying time for Union reinforcements to arrive, and later to occupy the vital ground of Cemetery Ridge. Early Union reinforcements initially defended north and east of the town. These Union forces at first held; however, subsequent Confederate attacks in greater strength forced Union defenders to retreat through the town of Gettysburg. They did so to positions on the northern end of Cemetery Ridge and Culp’s Hill, which eventually formed the extreme Union right.

Day 2 included continued arrival of reinforcements for both sides; adjustments/extensions in positions; and Ewell’s demonstration against the northern part of the Union position (Culp’s Hill) as well as secondary attacks against the Union center by Hill. It ended with Longstreet’s afternoon attack against the Union left – including the famous and desperate fighting at the Peach Orchard, Devil’s Den, Wheat Field, and (most critically) Little Round Top. But at the end of the day, the Union lines – though badly battered – still held.

Day 3 of the battle started with an attack on the far right of the Union line (Culp’s Hill and the northern end of Cemetery Ridge) , with savage fighting for several hours. Then in the early afternoon came the battle’s culmination: a multi-division infantry attack on the Union center.

Pickett’s Charge.

The Assault.

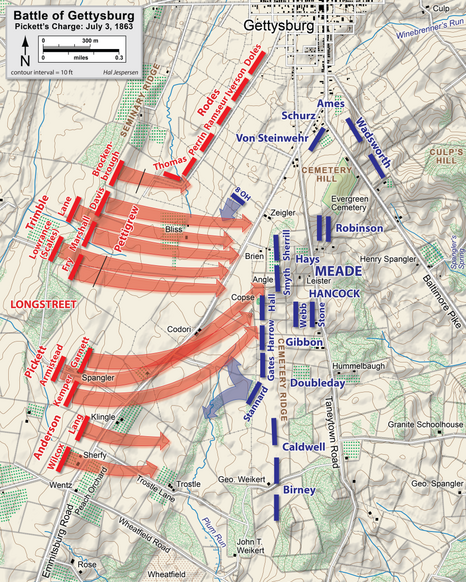

Map Depicting Pickett’s Charge (courtesy Wikipedia Commons ); Little Round Top is off the map to the south of the southern end of Cemetery Ridge)

The plan for the assault was simple: Confederate artillery would bombard a small part of the Union center with all available guns, battering it severely. Massed Confederate infantry would then assault that Union center, breaking it – and with it, the Army of the Potomac.

The infantry attack would begin from the present day locations of the North Carolina and Virginia Memorials on or near Seminary Ridge, attacking towards the center-right of the Union line. (The precise locations of these memorials are shown on this NPS map – it’s PDF, and It’s fairly large. They’re generally near the starting positions of Pettigrew’s and Pickett’s divisions on the above map.) The Confederate infantry would stay concealed as long as possible. It would then form, and assault the Union Center. The attack would involve three full divisions – roughly 12,500 men.

The precise location of the objective of the charge is in dispute. Suffice it to say that the area called “The Angle” – so named because it was formed by a right-angle of two stone fences – is close enough if not exact.

In their assault, the Confederate infantry would cross approximately 1,200 meters – about 3/4 mile – of open, gently rolling terrain. It would then assault, uphill, into a fortified Union line.

As it turns out, the Confederate infantry would also attack largely without artillery support once preparatory fires had been completed. Though the Confederate artillery preparation was massive – 150 to 170 guns, reputedly the largest artillery concentration of the war to that date – the Confederate Army was short on artillery ammunition. It fired most of its ammunition during the preparatory fires.

The attacking Confederate infantry would pass in and out of view of both the enemy and their comrades as they crossed undulating ground.

They would cross a significant obstacle – a fenced, sunken road (Emmitsburg Road) – at about the time they came into rifle range of the enemy.

They would assault while receiving heavy fire from both Union artillery and infantry – firing largely from covered and at least partially-concealed positions – from both flank and front. As it turns out, the Confederate preparatory fires were not particularly effective. Moreover, much of the Union artillery deliberately ceased fire during the Confederate preparatory fires, feigning destruction – until after the Confederate preparatory fires were over and the infantry assault had begun.

Should you want an overview of what the average Confederate infantry soldier in Pickett’s charge saw as he assaulted the Union lines on that fateful day, Andrew Weigel has an excellent site that details both main assault routes in photographs. On a pleasant day, either route is about a 1/2 hour one-way stroll. Since the first part of the “charge” was at a route-step march, it likely didn’t take all that much less time on 3 July 1863 either – probably about 20 minutes or so).

But that’s 20 minutes or so while in the open, exposed – and under murderous enemy fire. In other words: it was about a 20 minute stroll through hell. Each way.

The Battlefield.

Here’s the terrain the Confederate infantry would cross, as seen in 2009 from the Virginia Memorial (from Weigel’s site):

And here’s the view from the North Carolina Memorial – again, courtesy of Weigel’s site:

Here’s the view from the center of the Union line, near The Angle:

(image from Wikipedia commons)

A photograph of what the Union forces on Little Round Top saw, looking northward at the right flank of the Confederate assault, may be found here; more photographs of the battlefield may be found at the same site here. (These are actual photographs taken during or shortly after the battle.)

Cross that, under fire? Even in the 1860s, that would be close to suicide.

For many, it was. Yet they still tried.

Union artillery raked the Confederate flank from Little Round Top during Pickett’s Charge with murderous effect, probably using both solid shot and canister. Union artillery on Cemetery Hill to the north of the Union center (no photos available) similarly pounded the left flank of the Confederate attack. Union artillery in the line raked the troops from the front. And when they came within range, the Union infantry deployed along Cemetery Ridge engaged them with rifle fire.

The Confederate infantry crossed the fenced road (Emmitsburg Road), then assaulted uphill. Some reached the crest of Cemetery Ridge north of The Angle, briefly causing a small break in the Union line. But only a few from Armistead’s Brigade of Pickett’s Division made it that far. And Union reinforcements quickly arrived to seal the breach.

The Confederates were then forced to retreat. And retreat they did, under fire, over the same 1,200 meters (3/4 mile) they’d crossed shortly before.

The culmination of Pickett’s charge is often referred to as “the high water mark of the Confederacy”. A monument so named is found at Gettysburg on this spot.

The name is apt. After Gettysburg – and after the Pyrrhic tactical victory but strategic failure at Chickamauga a bit over two months later – the Confederacy would never again have the capability to threaten the Union seriously.

Pickett’s Charge Considered.

The Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava occurred less than 9 years before Pickett’s Charge. It was (and still is) renowned for both its high casualty rate and the extreme courage shown by the attackers. Casualties among the Light Brigade (killed/wounded/missing) were approximately 40% – 287 casualties in approximately 670 participants.

So what, then, are we to make of Pickett’s Charge?

At the beginning, the participants in Pickett’s Charge numbered 12,500. Less than 6,000 made it back uninjured.

The total casualty rate among all Confederate forces in Pickett’s Charge was roughly 52% – 6,551 casualties out of approximately 12,500 participants. Less than half of those who began the attack returned whole.

Among the Confederate attackers, Pickett’s division fared the worst (this sad fact likely led to the name for this action). In Pickett’s division, total casualties exceeded 60%. And as a group, the senior officers in Pickett’s division fared as badly – or in some cases, worse – as did their men.

- All 3 of Pickett’s brigade commanders were casualties: 2 were mortally wounded (Armistad, Garnett), while one (Kemper) was wounded and captured.

- All 13 of Pickett’s regimental commanders (100%) were casualties.

- Of the 40 field grade officers (MAJ-LTC-COL) in Pickett’s division, 26 were casualties (65%).

At Balaclava, the charge was made by mounted cavalry. Presumably most of the survivors departed the battlefield relatively quickly.

Pickett’s Charge was an infantry engagement; it was done on foot. Including the fighting, it took the best part of an hour – not counting the artillery preparatory fires. And it also included a withdrawal -but slower and on foot – while under enemy fire.

A massed infantry attack, over 3/4 mile of open country, into the teeth of a prepared position, largely without support, while under fire. When you think about that, it sounds . . . . unbelievable. Simply unbelievable.

Yet that day, the unbelievable happened. And it came within a whisker of success.

Should you have the chance, it’s worth your while to visit Gettysburg. I have twice before, and I plan to do so again next summer. But next time, if I can I believe I’ll walk both routes of Pickett’s charge – if for no other reason than to honor the memory and bravery of those who did the same nearly 150 years ago.

Category: Historical, Real Soldiers

Excellent writeup! I was thinking about getting up there for the 150th next year, but I have a sneaky suspicion that its going to be a mess. Perhaps next summer.

Good work, thanks for this.

There is an excellent book on this titled “Pickett’s Charge in History and Memory” written by a history professor at Penn State. She gets into how the action became known as “Pickett’s Charge” (this gets into the disputes between Virginia and North Carolina-primarily-veterans for years after the war). She also talks about how it is dangerous for a historian to take first hand accounts as gospel. In one instance she points out how it would have been impossible for a memoirist to describe an action he claims to have seen given his position on the battlefield and the lay of the land.

In any event as horrible as “Pickett’s Charge” was Hood’s suicidally inept attack on the Union position at Franklin was probably worse. Sadly that battlefield is not as we’ll preserved as Gettysburg (not by orders of magnitude) and so you don’t get the same sort of experience visiting there,

The NC/VA rivalry was doubtless part of the reason, 68W58. So was the sad fact that both Trimble’s and Pettigrew’s careers ended shortly after Gettysburgh – Trimble’s by being seriously wounded and captured and Pettigrew’s by being KIA 2 weeks later. The fact that Richmond newspapers were a primary publicity organ for the Confederate government due to their location in the Confederate capital also certainly played a part.

Hondo – great synopsis and a refreshing change from TAH norm. Thank you!

From a professional perspective, while I respect the cajones of the men who fought on both sides (the battle was hand-to-hand for a time), any engagement in which Americans take 52% casualties is deplorable.

While Pickett’s Charge is settled history, the what-ifs – such as securing Hanover, or using Pendleton’s Reserve Artillery elsewhere – are fun to consider.

Superb article – thank you for posting it! When I returned from Southern Watch in ’95, we went to Gettysburg for a few days, and my son and I walked as much of Pickett’s Meadow as we could, right up to the High Water Mark. That may be the best way to appreciate what happened that day.

Mike

Great analysis. Scale and context of great historical engagements seems to be a great mystery to society at large today, leading to repeated blunders and defeats. Cemetery Ridge was not the Russian Battery at Balaclava. It was the Thiepval and the Schwaben Redoubt on the Somme. It was something that the Confederates, unlike the British of the Great War, could not sustain.

Thanks for the post. Right up my Alley. I’ve been to Gettysburg twice. Once for the 135th Anniversary reenactment (which was near the park but not on it) as a participant and twice more as a tourist for a few days each. It takes a good three days to do as semi decent tour.

I’ve walked the field over the route of Picket’s charge with a period uniform and gear,,, pretty tiring,I imagine it would have been horrible with projectiles flying.

The name “Pickett’s Charge” came more from the Newspaper coverage. The Richmond Paper, of course, focused on the troops from Va. Pickett also had the largest Division as the others had seen hard fighting the first two days.

In retrospect, as mentioned above by 68W58 Franklin was worse. The entire battle of Franklin was nothing but a suicidal charge by Confederate. More Men (19,000) over a larger distance (2.5 miles) for a longer time (5 hours) and more casualties ( 7,400).

Franklin was not preserved nearly as well as Gettysburg, if fact until recent preservation efforts a pizza hut stood on the ground where one of the 6 Confederate Generals fell ( Cleburne.

Back to Gettysburg. If you haven’t been,,,go. The ifs ands or buts of what could have happened and the debate whether or not that it was the high tide of the Confederacy nonwithstanding, its the best NPS battlefield we have.

I plan on attending the Second Armored Cavalry Regimental reunion next October-held in Gettysburg. I haven’t been there in over 45 years.

Supposedly at Appomattox, Lee told Grant “The only reason you won at Gettysburg,was that you had more Irish”.

I’m no Civil War buff but over the years I ‘ve been there many, many times. I like to go in winter when the tourists aren’t about and I can be alone there to walk places otherwise not usually walked.

Hondo, thanks for the awesome and detailed description. I have been there many times and walked the entire battlefield. It is a moving experience. I have tried to imagine the thoughts those soldiers had when marching in formation out of the woods on Seminary Ridge, across an open field while being bombarded with artillery and mortars, then small arms when they began to close.

You are correct that it is a 20-30 minute trip across mostly open ground. The objective is in dispute but the Angle or the nearby Ziegler’s Grove are the most likely, not the hollywood-hyped copse of trees that were probably too short in 1863 to be seen from the Confederate lines. If one has the time and interest there are many important Civil War battlefields within an hour of Gettysburg, for instance Antietam and Manassas. Just a bit further south Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and the Wilderness.

Thanks again for sharing this.

Great article Hondo! I was able to stop once and took my daughters and wife through the driving tour. I have a few relatives including two g-g-grandfathers who fought there, one in the 11th GA who were at Devils Den and one in the 18th NC in Lane’s Brigade that participated in Pickett’s Charge. It was very sobering to see the battlefield and think what it must have been like to fight in those places. The discipline it had to take to maintain formation and continue to advance under such withering fire demands respect. I really enjoyed reading the book on the battle by Stephen Sears. To me he does a great job at personalizing the battle the way Cornelius Ryan did with WWII. I hope to get back there some day soon when we go back to Jersey to see my wife’s family. I had always wanted to jump in on one of the staff rides that were done there in the past, but from what I hear they don’t do that anymore. Always wanted Gettysburg on my jump log.

As much as I despise the University of Mississippi (as I am a Mississippi State alumnus), credit where credit is due to the University Greys. Company A of the 11th Mississippi was comprised of almost the entire student body of Ole Miss and they were wiped out atop Cemetery Ridge. I imagine my Ggggrandfaher was watching from his position on the left flank with Rodes.

I imagine most of you have read it, but, if by chance you haven’t, you owe it to yourself to read The Killer Angels, a historical novel by Michael Shaara. It is probably my favorite book, and it details the Battle of Gettysburg from a character driven perspective that is both entertaining and educational.

Great post Hondo

Sorry, fat thumbs and little buttons do not a spelling champion make.

What amazes me, especially after attending the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Fredericksburg last weekend, is that Lee thought it was a good idea to send his men across an open field broken by an obstacle (the road and fence) and then up a hill at men behind a wall when just a few months earlier he had butchered Union troops by making them cross an open field broken by an obstacle (a mill race) and then up a hill at men behind a wall.

The decimated ranks of the Confederate infantry hit the Angle at a bad spot too, it was defended by the ‘Philadelphia Brigade’, the 69th and 71st Pennsylvania Volunteers, recruited from the rough and tumble crowd of Irish immigrants that packed Philly’s inner cities at the time. The 71st on the right flank broke, but the 69th stubbornly held on, fighting hand to hand with muskets, knives and fists, but were slowly forced back. Concentrated, double loaded canister shot from Battery A, 4th US Artillery under LT Alonzo Cushing’s troops (who had refused to withdraw when they had a chance) broke the back of the Confederate troops pouring over the wall. The remnants of the Rebel Infantry then overran the battery, killing the young officer and the majority of his men, but the damage was done. Union reinforcements quickly arrived to plug the gap, forcing the surviving Southerners to retreat.

That’s the less known story of how a brave young West Pointer and a bunch of hellaciously stubborn (redundancy?) Irishmen helped hold the Union lines.

ANCCPT-glad you mentioned Cushing, who was posthumously awarded the MOH just recently. His brother was a naval officer who is also worthy of the award for his exploits in sinking the ironclad CSS Albemarle. The younger Cushing was called “Lincoln’s commando” for his exploits.

I remember visiting Gettysburg when I was 15 years old with my Boy Scout troop. We visited the Virginia memorial, and then our scoutmaster had us form up and march along the route of Pickett’s Charge. He described the artillery and rifle fire aimed at the Confederate infantrymen, yelled at us when we fell out of formation, and as we got close to the Angle, he then yelled at us to charge the Union lines.

As a teenager, it was fun to run and goof around with your buddies. Ten years on, I revisited the site of the battle with my friends and the full impact of what they did hit me like a bag of bricks. People can say it was the “high water mark” of the Confederacy, but I say it’s the high water mark of courage.