2012 FBI Data Says: More BS from the Brady Bunch

In a previous article, I published an analysis of the apparent linkage between a state’s Brady Score on that state’s overall and firearms murder rates. Essentially, that analysis showed that BS is indeed an apt abbreviation for the Brady Score – at least regarding the thesis that a higher Brady Score leads to lower murder rates.

The modern-day “Brady Bunch” (AKA the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence) has released a new version of it’s Brady Score metric (2011). The FBI has released 2012 crime data. So it seems to me that it’s time for a re-look.

Obligatory warning: the article’s a bit longish. And yeah, there’s math involved. (smile)

Introduction

In case anyone’s been living under a rock: the Brady Bunch is a group of anti-gun zealots whose primary aim in life is to remove guns from US society, rights guaranteed by the 2nd Amendment be damned. Their basic thesis is that less guns will lead to less gun crime – and, presumably, thus to less overall violent crime.

Their “Brady Score” is a numeric measure of how restrictive a state’s gun laws are regarding the legal purchase, possession, and concealed carry of a firearm. The Brady Score appears to be a credible measure of exactly that: a higher Brady Score is indeed associated with more restrictive firearms laws at the state level.

Given the above and access to violent crime data on a state level, the Brady Bunch’s thesis is testable. One mechanism would be to check for the correlation between state Brady Scores and the rates of violent crime within a state. If it were possible to ascertain the fraction of violent crimes committed using firearms, that would even allow testing of related thesis: (1) that a higher Brady Score would reduce the fraction of violent crimes committed with firearms, and (2) that a higher Brady Score would reduce the rate of violent crimes committed using firearms.

Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) data available from the FBI provides enough information to ascertain precisely this breakout for three serious crimes: murder/non-negligent homicide, robbery, and aggravated assault. Combined with state Brady Scores and a deemed Brady Score for the District of Columbia equal to that of New York State (the Brady Bunch doesn’t publish a Brady Score for DC), exactly such an analysis is possible.

Methodology

The methodology used was essentially that used in my previous article, with the exception that the FBI was a direct data source for the current analysis (a third party collected and published some of the data I used in my previous analysis). However, in my current analysis I performed more detailed statistical testing for significance than previously. I will discuss that further below.

I conducted the analysis which follows for four categories of crimes: (1) overall violent crime, excluding forcible rape and arson; (2) murder and non-negligent homicide; (3) robbery; and (4) aggravated assault. Forcible rape and arson were not included in the analysis.

Arson was excluded from analysis as it is a relatively rare crime; the FBI does not include arson in the UCR national and by-state data reporting (it was not included in 2012 FBI data). I excluded forcible rape because while forcible rape is included in UCR violent crime statistics provided by the FBI as one of the four crimes making up the overall category of violent crime, the FBI does not include supplementary data for rape indicating firearms usage. It is thus impossible to determine either the fraction or rate of forcible rape that involved use of a firearm. Due to the lack of this supplementary data, I could not analyze the crime of forcible rape on the same basis as the other three major components of violent crime: murder and non-negligent homicide, robbery, and aggravated assault). I thus elected to omit it vice conduct a partial analysis that did not include firearms use data.

As noted above, the Brady Bunch does not publish a Brady Score for the District of Columbia. I did not have time to research DC’s firearms laws (generally acknowledged to be among the most restrictive in the USA) and calculate a Brady Score for DC using the Brady Bunch’s methodology. Instead, I deemed DC roughly equivalent to New York state in terms of restrictive firearms laws and arbitrarily assigned DC a Brady Score of 62 – the same as New York. I used that value as DC’s Brady Score in subsequent analysis.

A Bit of Statistical Background

The Brady Bunch implies a cause-and-effect relationship between the availability of guns and violent crime. Their thesis is that more restrictive gun laws will reduce gun crime – and thus will also reduce overall violent crime.

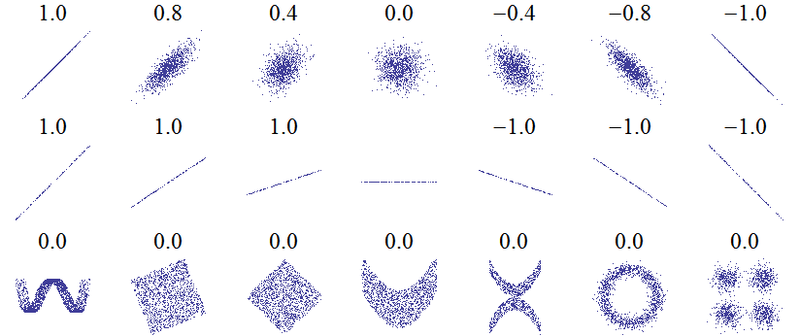

Real-world data allows testing this hypothesis. This can be done by calculating the correlation coefficient between state Brady Scores and observed violent crime rates. The correlation coefficient is a measure of how closely a linear model – generally considered the simplest direct cause-and-effect model – fits observed data. Correlation ranges from -1.0 to +1.0; a value of is +1.0 or -1.0 represents data that lies exactly along a straight line, while a value of 0.0 represents data that shows no relationship to a straight line (though it may have a different but nonlinear structure). This is visually illustrated in the plots below. In these plots, correlation coefficients are given above each diagram for which correlation is defined (the correlation coefficient for a horizontal line is mathematically undefined):

Correlation is thus a measure of how well a direct, linear cause-and-effect model represents reality. The closer the absolute value of observed correlation is to 1.0, the better the fit.

The sign of the correlation coefficient is also important. A negative correlation between Brady Score and violent crime rate means that a higher Brady Score is associated with a lower violent crime rate; a positive correlation shows the opposite (e.g., a rising Brady Score is associated with a rising violent crime rate). If the Brady Bunch’s thesis is correct, states’ violent crime rates – and in particular, states’ firearm violent crime rates – will show a negative correlation with states’ violent crime rates.

How Meaningful Are the Results?

In any process using statistical sampling there is always the possibility that random factors may have resulted in a sample that is not representative of the underlying population. In layman’s terms: there’s always the chance you got a “hinky” sample that just doesn’t reflect reality.

Fortunately, there are ways to determine the chances that a sample is “hinky” and that the results are misleading. This is done using statistical hypothesis testing.

A full discussion of statistical hypothesis testing is well beyond the scope of this article. However, the short version is that for correlation it’s possible to determine the chances of accepting a “hinky” sample. Further, this determination is based on two easily obtained values about the sample: (1) the number of pairs used to calculate the correlation coefficient, and (2) the value of the correlation coefficient obtained by using those pairs. That chance of making an error and accepting a result based on a “bad sample” and leading to an inaccurate result is typically called the test’s “confidence level”. For confidence levels, obviously smaller is definitely better (a 1% chance of making an error is MUCH better than a 10% chance – but typically requires much more data).

The quick and easy six-sigma significance test for correlation discussed in my earlier article is the equivalent of test for significance at the 0.1% level. (I have operationally confirmed this result using this test for correlation coefficient significance provided by vassarstats.net.) This means that decisions made regarding correlations using a result of significance of YES (result >3) using this simple test have approximately a 0.1% error rate – or a risk of being wrong about the correlation being real in such cases of roughly 1 in 1,000.

Testing involving a t-statistic calculated from the sample and the Student’s t-distribution is also often used at lower levels of significance and with smaller samples. The 5% significance (1 in 20 chances of accepting a nonexistent correlation) and 10% significance (1 in 10 chance of accepting a nonexistent correlation) are commonly-used thresholds. (Six sigma uses such a high threshold – 0.1% significance, or 1 in 1,000 chance of error – because changing production processes in an industrial operation are typically expensive. Since laws are also often rather expensive to implement, one can argue lawmakers should also demand data approaching that level of significance indicating that a proposed new law will have the desired effect when considering new laws.)

Results of Analysis

Results of statistical analysis are presented below. Data used was processed using the statistical functions of MicroSoft Excel.

Violent Crime

Per UCR reporting standards, violent crime is defined as the total of four separate offenses. These four offenses are murder and non-negligent homicide; forcible rape; robbery; and aggravated assault.

A total of 50 jurisdictions (49 states plus DC) reported UCR violent crime data to the FBI. A total of 46 jurisdictions (45 states plus DC) provided sufficient supplementary data to allow determination of firearm violent crime fraction and rate. Alabama, Florida, and DC provided insufficient data to determine their respective firearms murder fractions; Illinois provided insufficient data to determine its robbery firearms fraction and rate on a statewide basis. (Minnesota did not report rape information; however, Minnesota did provide enough data to determine its firearm violent crime rate.)

As discussed above, forcible rape was not included in this analysis as the FBI does not provide any breakdown on the use of firearms during forcible rapes; it is thus not possible to determine firearm usage associated with the crime of forcible rape (the intent of this study is to analyze the effect of firearms laws on both violent crime in general and firearm violent crime in particular). However, data on forcible rape is necessary to determine a state’s overall violent crime rate, which in turn is needed to determine a state’s firearm violent crime fraction.

When forcible rape was excluded (see above for rationale), a state’s violent crime rate, firearm violent crime fraction, and firearm violent crime rate in 2012 was found to be positively correlated with states’ Brady Scores. This implies that a rising Brady Score is linked, statistically speaking, with rising rates for these three quantities.

None of the correlations observed were significant at the 0.1%, or 5% significance levels. However, the overall violent crime rate’s correlation with Brady Score was significant at the 10% level. (The actual level was 5.09% – less than 0.1% outside the limit for 5% statistical significance).

These results imply that there is a moderate–to-strong linkage between an increasing Brady Score and an increasing violent crime rate. It also indicates a possible lesser degree of linkage between an increasing Brady Score and both increasing violent crime firearm fraction and firearm violent crime rate.

In layman’s terms: laws that make it more onerous and difficult for law-abiding citizens to own firearms are NOT inked with a lower rate of violent crimes – period. In fact, it appears such laws tend to increase the rate of violent crime, statistically speaking.

This behavior is fully explainable by considering the criminal as a rational actor. Onerous and burdensome firearms laws disarm the law-abiding populace to a greater degree than criminals; this explains the positive correlation between firearm violent crime fraction and Brady Score. In localities where firearms are more difficult to obtain, criminals also have a higher chance of encountering an unarmed victim – and thus a greater relative chance of success, whether or not armed. The effect appears more pronounced among criminals who commit violent crimes without using firearms, as they now have less chance of encountering an armed victim (and thus a higher chance of success and less risk of their own life). In contrast, a criminal intent on using a firearm is more likely simply not to care about local laws and acquire one if he/she can. This explains both the higher correlation for violent crime and the relatively more modest correlation observed for firearm violent crime fraction and rates.

Murder and Non-Negligent Homicide

The crime of murder and non-negligent homicide is defined by UCR reporting standards as “the willful (nonnegligent) killing of one human being by another.” It is one of the four crimes making up UCR violent crime. Justifiable and accidental homicides are excluded from the definition of murder and non-negligent homicide; the same is true for suicides.

Three jurisdictions (Alabama, DC, and Florida) did not provide sufficient data to determine firearms usage during homicides occurring in these jurisdictions. They are thus excluded from consideration in firearm fraction and firearm rate calculations. Since overall rate data was available, these jurisdictions were considered in overall rate calculations. Illinois only provided partial data. However, since that data concerned approximately 2/3 of homicides occurring in Illinois, that data was taken as representative of the state as a whole.

Murder and non-negligent homicide rate, firearm fraction, and murder and non-negligent homicide firearm rate in 2012 were all found to be positively correlated with states’ Brady Scores. This implies that a rising Brady Score is linked, statistically speaking, with rising rates for these three items. However, the linkage for firearm murder rate, though positive, is also so small (a correlation coefficient of less than 0.01) as to be essentially nonexistent.

None of the correlations noted were significant at the 0.1%, or 5%, or 10% significance levels. These results imply that there is at best only slight linkage between an increasing Brady Score and an increasing murder and non-negligent homicide rate or murder and non-negligent homicide firearm fraction, and essentially no linkage between Brady Score and murder and non-negligent homicide rate. However, the fact that all of these correlations are positive indicates that any claim of linkage between rising Brady Score and lower rates of these three quantities is more likely false than not – and in the case of the first two, roughly 3 to 4 times as likely to be wrong.

In layman’s terms: laws that make it more onerous and difficult for law-abiding citizens to own firearms are NOT inked with a lower rate of murder and non-negligent homicide – period. In fact, it appears such laws tend to have either no impact or to increase modestly the overall incidence of murder and non-negligent homicides, statistically speaking.

This behavior is also fully explainable by considering the criminal’s motivations. In case of murder or non-negligent homicide, the criminal either acts intentionally and in a calculating manner, or acts irrationally due to rage. In the former case, the criminal concerned has already decided to act unlawfully and will thus not care about the law whatsoever; local firearms laws will have little or no effect on their behavior. The only restraining effect will thus be their fear of encountering a victim who can resist effectively – hence the modest positive linkage between rising Brady Score and both overall murder and non-negligent homicide rate and firearms fraction. In the latter case (rage), perpetrators are acting irrationally; in this case as well, local firearms laws will have no effect on their behavior. In either case (but particularly the latter), other factors besides choice of weapon will dominate. Thus little effect of local firearms laws on firearm murder rate would be expected.

Robbery

The crime of robbery is defined under UCR reporting standards as “the taking or attempting to take anything of value from the care, custody, or control of a person or persons by force or threat of force or violence and/or by putting the victim in fear.” It is one of the four crimes making up the category of violent crime.

Illinois did not provide sufficient supplementary data regarding firearms use in robberies (unlike murder, Illinois provided supplementary data on the use of firearms for less than 5% of robberies occurring in 2012). Thus, for robbery firearm fraction and firearm robbery rate Illinois was excluded from correlation calculations.

Based on 2012 FBI UCR data, robbery rate, firearm fraction, and robbery firearm rate were all found to be positively correlated with states’ Brady Scores. This implies that a rising Brady Score is linked, statistically speaking, with rising rates for these three items.

In two cases – overall robbery rate and firearm robbery rate – the correlations noted were significant at the 0.1% levels. These results imply that there is unmistakable true linkage between an increasing Brady Score and increasing robbery rates and firearm robbery rates. Claims to the contrary for these two crime rates are so unlikely to be correct (less than 1 chance out of 1,000) that they should be regarded as wishful thinking or fiction. The data further shows a weaker (though still significant at the 16% level) positive correlation between firearm robbery fraction and increasing Brady Score.

In layman’s terms: laws that make it more onerous and difficult for law-abiding citizens to own firearms are definitively linked to higher rates of robbery in general and in particular to a higher rate of robbery using a firearm. They also appear linked – though more weakly – to a higher fraction of robberies committed by perpetrators using firearms.

Common sense explains these results. Robbery is an intentional serious criminal act. The robber seeks an advantage over his/her potential victim and has already determined they will break the law; they are thus not concerned with nor are they particularly affected by local laws restricting firearms ownership. As a result, a disarmed population provides easier “target set” for potential robbers; robbers armed with a firearm gain a larger advantage. The result is eminently predictable by anyone other than those who believe in unicorns flying to the rescue.

Aggravated Assault

Aggravated assault is the last of the four crimes making up the category of violent crime. It is defined as “an unlawful attack by one person upon another for the purpose of inflicting severe or aggravated bodily injury.”

As with robbery, Illinois did not provide sufficient supplementary data regarding firearms use in aggravated assaults (unlike murder, Illinois provided supplementary data on the use of firearms for less than 5% of aggravated assaults occurring in 2012). Thus, for aggravated assault firearm fraction and firearm aggravated assault rate rate Illinois was excluded from correlation calculations.

Aggravated assault provided the most complex results of crimes analyzed. Overall, the aggravated assault rate was found to be essentially uncorrelated with Brady Score (the observed correlation coefficient was positive, but was less than 0.01). However, the aggravated assault firearm fraction and firearm rate were both observed to be negatively correlated with Brady Score – the former was found to be significant at the 10% level, while the latter was not. This led to examination of the correlation of non-firearm aggravated assault; this was found to be weakly positively correlated with rising Brady Scores

In layman’s terms, this means that there is no observable linkage between a state’s overall aggravated assault rate and Brady Score – in essence, that the rate of aggravated assault is not affected by a state’s firearms laws. However, restrictive firearms laws may lead criminals to substitute other weapons for firearms by making them less readily available.

This result is explained by considering human nature. Much like murder, aggravated assaults are due to two causes: either a premeditated attempt to seriously injure, or “losing it” due to rage. In the former case, restrictive firearms laws will have no effect on the method chosen; committed criminals will obtain and use firearms if they desire to do so. However, aggravated assaults falling into the “crime of passion” category will likely be committed using any weapon at hand, particularly in domestic violence situation. This means that a lower incidence of firearms availability may cause more of these aggravated assaults (which will be committed regardless) to be carried out with knives, blunt instruments, or hands. The result will still be serious bodily injury, unfortunately – but not via gunshot. Under this scenario, a large majority of aggravated assaults being “crimes of passion” would explain the observed results.

Conclusions

1. Violent crime (less rape) was studied using FBI 2012 UCR data to determine the correlation between various violent crimes (and violent crime, rape excluded, overall) and a jurisdiction’s firearms laws. Brady Score was used as a measure of the restrictiveness of a jurisdiction’s firearms. Forcible rape was excluded from consideration as no data was available regarding the use of firearms during forcible rapes.

2. Restrictive firearms laws (as measured by a jurisdiction’s Brady Score) appear to be associated with higher overall violent crime rates (rape excluded), not lower. The linkage is strong (just outside 5% statistical significance) for overall violent crime. Less significant linkage was observed for violent crime (rape excluded) firearm fraction and firearm violent crime (rape excluded) rate.

3. Restrictive firearms laws appear to be associated with higher rates of murder and non-negligent murder and a higher percentage of murders committed using firearms. The linkage is weak for both overall murder rate and firearm murder fraction. There is essentially no observable linkage between firearm murder rate and restrictive firearms laws.

4. An undeniable (<0.1% significance level, or less than 1 chance in 1,000 of being wrong) correlation between more restrictive firearms laws and higher robbery and firearm robbery rates was observed. A weaker (but still above the 20% significance level) linkage between restrictive firearms laws and a higher fraction of robberies committed using firearms was also observed.

5. Essentially no linkage was found between overall aggravated assault rate and restrictive firearms laws. There does appear to be a link between restrictive firearms laws and a lower rate of aggravated assaults committed using firearms and a lower fraction of firearms usage during aggravated assaults. However, this is suggestive of restrictive firearms laws causing a substitution of weapons vice an overall depression on a jurisdiction’s rate of aggravated assault.

6. Bottom Line: more restrictive firearms laws do not reduce the rate of violent crime. If anything, they may actually raise the rate of violent crime.

And, finally:

7. BS appears to remain an appropriate abbreviation for the term “Brady Score” – at least regarding the Brady Bunch’s thesis regarding firearms and violent crime.

Data used and calculated parameters determined during this study may be found here. Original data sources are identified therein in notes following calculated parameters.

Category: Gun Grabbing Fascists, Guns, Legal

The incidence of rape should NOT be excluded from the analysis, nor should that correlation to tied solely to the use of firearms during the commission of the crime.

The State of Illinois does provide records on crime, including in Chicago, but that data does not conform to FBI UCR standards (probably on purpose, to get it excluded from the reporting), particularly on rape statistics.

An example of the reason why rape should be included is that the potential that the rape victim is armed is a strong deterrent to the criminal. Following the passage of Florida’s Stand Your Ground law, through the Martin-Zimmerman incident, rape declined (steadily by a total of) 25% in FL. A great percentage of those rapists are unarmed.

Guess we will need to get back to this later, Hondo. Making book on the current doings in DC is just more fun for now. Sorry.

Helloooooo Jesse helloooo. Where are you?

All that to tell me more anti-gun laws are less effective in lower crime?

Geez, Hondo, I could have said the same thing in 10 words or less.

Ooops! I already did. I only used 9 words. 🙂

can’t analyze data that isn’t there… he says above that rape is excluded because the FBU does not break out rape-with-firearm from rape-w/o-firearm and he doesn’t want to just make stuff up a la the Brady folks.

David: The FBI does report rape statistics and IL reports theirs separately. The data from FL indicates there is a relationship between right to carry laws and decreased incidents of rape. The question is NOT whether the criminal was armed, but whether the potential victim being armed was a deterrent, or not.

I will contend that if right to carry laws decrease the likelihood of rape, or violent crime in general, whether or not firearms are used by the criminals, then right to carry laws are a positive impact on society.

TN – I believe his statement was not that rapes were not reported, but that they were not separated by whether the rapist used a gun or not. If they are indeed broken out like that, might want to share that with Hondo – unless I misread his third Methodology paragraph, he claims otherwise.

David is correct. The FBI’s UCR statistics include data regarding reported forcible rape. However, as far as I can tell the UCR supplemental data available from the FBI for rape DOES NOT include a breakout by weapon used by the perpetrator (if it does, it’s certainly well hidden – I haven’t been able to find it). In contrast, the UCR supplemental data for murder and non-negligent homicide, robbery, and aggravated homicide available from the FBI DOES include a breakout by weapon used – by the perpetrator.

As far as I can tell, NONE of the UCR data includes information on weapons use by a victim – only by perpetrators. I did find some rather ambiguous data about justifiable homicides, but that hardly appears to be the full story.

Unless one is willing to MSU (make stuff up), it’s kinda hard to analyze data that simply isn’t there.

At the risk of oversimplifying things, might I proffer that since these are crime statistics, the accumulation of data on victims of crimes, while interesting, is not the first thought that the bureaucrats consider?

Damn I hate it when the gun grabbers are once again shown to be full of crap.

@Hondo I know that The Detroit police department has been caught in the past for listing unsolved (read: never investigated) homicides as justified to clear their case log.

I realize that this would prove to be a minuscule change in an already consulted data pool, but I can’t bring myself to believe that they are the only PD doing this.

*convoluted not consulted

Autocorrect is the bane of my existence.

David/Hondo: I am not contending that the FBI includes statistics on weapons used in the commission of a rape.

I am contending that the analysis should also assess whether there is a relationship between gun right to carry laws (or low BS scores) and decreased rates of rape, period, whether or not the criminal used a weapon.

As I pointed out in an earlier comment: In the years between FL passing the Stand Your Ground law, and the Martin-Zimmerman case, Rape in FL decreased by 20%. The question remains: is that relationship replicable across the nation? Or is it a statistical anomaly?

Actually, as I recall, the FL statistics did include “weapon” used by the perpetuators, and surprisingly to me, it was often “none.” An unarmed attempted rapist would of course be taking a considerably greater risk if more women were armed.

Also, as I stated earlier, if less gun control laws decrease rape by even 10%, and the all other violent crime remains unchanged, then increasing gun possession by law abiding citizens has a net positive effect.

TN: actually, what you observe (that no weapon is often used in rape) does NOT surprise me – given the rather convoluted definition under UCR rules for the crime of forcible rape. To begin with: under the UCR, the crime of rape is gender-specific. Only male-on-female rape is considered “forcible rape” for UCR reporting purposes. Male homosexual rape is, absurdly IMO, NOT considered rape at all but is included as a type of “aggravated assault” or “sexual crime” instead. (I presume that the same is true of female homosexual rape and female-on-male rape, but FBI definitions are not explicit regarding those variants.) http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2012/crime-in-the-u.s.-2012/violent-crime/rape If only rape perpetrated by males on females is considered, the lack of a weapon in many if not most cases is not to me particularly surprising. If I recall correctly, the average US male is 5′ 9″ and about 170 lbs (or maybe larger; my recollection is from looking this up several years ago, averages may have changed since I looked that up, and humans have grown consistently larger since the 1500s). In contrast, my recollection is that the average US female is about 5′ 4″ and 120 or so lbs. Males also have proportionally more muscle mass than do females of the same size and weight – and are thus generally substantially stronger than a woman of the same size and weight. The average male can thus physically overpower most females he meets. A second reason that often no weapon is involved is the fact that, even in jurisdictions without restrictive laws, firearms ownership is largely a male phenomenon. It appears that most women still simply do not feel comfortable around and/or own firearms. Thus, there is less perceived need on the part of a potential rapist to be armed during the crime – even in areas where firearms laws permit virtually unlimited firearms ownership. Even in such locations, because of this fact the odds are still in an unarmed potential rapist’s favor. Finally, it is my understanding that many (if not the majority of) rapists know their victims and gain access to their victim’s… Read more »

Let me see…facts – vs – emotions…

I wonder which the agenda-driven anti-gun bureaucrats, both public and private, will base their arguments on?

I wonder…but not for long.